Proposal

Background

The Smith–Waterman algorithm solves the problem of local sequence alignment: given two sequences, it identifies the best matching pair of substrings by computing an optimal alignment score based on a user-defined scoring scheme. This includes a reward for character matches, penalties for mismatches, and gap penalties for insertions or deletions. It plays a foundational role in bioinformatics, identifying similar regions between DNA, RNA, or protein sequences. Due to its quadratic time complexity and the massive scale of modern sequencing datasets—often involving sequences with billions of elements—Smith–Waterman becomes a major computational bottleneck in genomic pipelines. There are GPU-accelerated libraries, such as CUDASW++, that take advantage of parallelism to achieve large speedups.

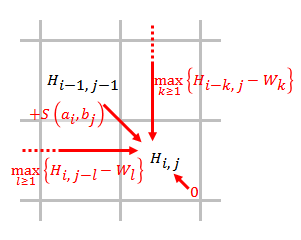

The algorithm’s structure makes it well-suited for this system, as it involves computing a 2D dynamic programming matrix where each cell $H_{i,j}$ depends only on its top, left, and top-left neighbors. As shown in the diagram, each cell is computed as the maximum of the match/mismatch score from the diagonal and possible insertion or deletion scores from the top or left, adjusted by gap penalties. This regular, local data dependency pattern provides a lot of opportunity. where processing elements (PEs) are arranged in a 2D grid and communicate only with neighbors in a rhythmic, pipelined fashion. Each PE can compute one cell and pass necessary values to adjacent PEs.

Figure 1: Data dependencies in Smith–Waterman algorithm.

Source: Wikipedia.

The SW algorithm is part of a bigger field of problems called sequence matching. These problems have large importance in bioinformatics - specifically DNA sequence matching. Real-world workloads are often very long sequences, making performance crucial, since the algorithm runs in quadratic time. In addition, real-world workloads can have sequences with a fairly sized alphabet - leading to large scoring matrices to determine the penalties for misalignment, adding another to keep track of. Finally, the problem can be extended to align multiple sequences at once, significantly increasing the workload, but adding another axis of parallelism across pairs of sequences.

Resources

We’d like to use AWS’s Trainium platform. This platform uses Trainium chips, which use the NeuronCore architecture and are based off of systolic arrays. The combination of multiple engines, fast interconnect, and multiple cores, makes these a perfect chip for running systolic array workloads. We’d need to get access (likely through credits) to the Trn1 AWS Trainium machines.

We’ll be using the Neuron Kernel Interface (NKI) language to construct our implementation, which provides some low-level contructs to make full-use of the NeuronCores. The library provides both high-level collective-communication abstractions and low-level CUDA-like reduction operations.

We’ll be starting from scratch, although there is the CUDA library for SW mentioned above. However, we believe our implementation will have to be much more customized and different in archiecture in order to make full use of the NeuronCore architecture. The SW algorithm is well documented in the original paper, however, and there many extensions. This paper (cited below) also provides a good high-level history and review of existing parallel methodologies for SW, and will be a good reference for comparison of our implementation.

Smith, T. F., & Waterman, M. S. (1981). Identification of common molecular subsequences. Journal of molecular biology, 147(1), 195–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5

Xia, Z., Cui, Y., Zhang, A., Tang, T., Peng, L., Huang, C., Yang, C., & Liao, X. (2022). A Review of Parallel Implementations for the Smith-Waterman Algorithm. Interdisciplinary sciences, computational life sciences, 14(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12539-021-00473-0

Platform choice

As mentioned above, we’ve chosen to use AWS’s Trainium & Neuron Kernel Interface because of its similarity to systolic arrays and other parallelism support. Dynamic programming problems are a good choice for systolic arrays because their memory model very closely models 2D DP problems. Those problems (and SW is no exception) have data dependencies on the array elements across their column/row (and sometimes elsewhere in the array, but in that case, usually very local). Systolic arrays are built upon the idea of passing data through (usually) an array of processors in a very similar way - recieve updates from adjacent node(s), do a bit of computation, pass it on - exactly the flow described for DP models.

The NeuronCore chips are well designed for our purposes. The V2, documented here, come with 4 engines: ScalarEngine, for highly parallelized 1-1 computations; VectorEngine, for highly paralleized M-to-N computations; TensorEngine: a 128x128 systolic array optimized for tensors and matrix multiplication; and GPSIMD-Engine, for more flexible and free-form vectorized operations. The memory hierarchy is software-managed and has 4 layers, which provides more opportunity to optimize data movement.

The Neuron chips’ TensorEngines (the systolic array based architecture) are optimized to be able to perform matrix multiplications and operations similar to matrix multiplications. However, combined with the other engines, we can achieve a variety of workloads. In addition, combining these engines will provide the best way to hide memory stalls and maximize throughput through pipelining. A key challenge, as described further below, will be to find the correct mix of workloads on engines to maximize speedup.

The challenge

One challenge is the algorithm itself. Smith-Watterman is traditionally a very iterative algorithm - there do exist CUDA implementations of it that are parallelized well, but our first challenge will be constructing an efficient version of the algorithm that can run in our systolic array setting. As mentioned in the previous section, the TensorEngine is the fastest due to the systolic array, but can only be used for a specific workload, so we’ll have to determine what the best way to convert as much of our problem as possible to that workload. Besides that, we’ll have to strike a good balance between the other engines, while not overloading one engine and sequentializing computation.

Another part of this will be working within the contraints of the NeuronCore chips, mainly constructing tiles corectly (they must be oriented correctly the “P” dimension restricted to a max length of 128, and within the restricted memory hierarchy). As mentioned above, the NeuronCore chips come with 4 engines, each optimized for a different purpose. One of the biggest challenges for this project will be determining the correct mix/utilizations of the engines to achieve the best speedup. In fact, we can implement SW on just the Vector/GPSIMD engines, using essentially SIMD operations + CUDA-style kernels. However, NeuronCores, are built to take full advantage of the TensorEngine, so our focus will be on moving as much computation as we can to the TensorEngines, while working within the limits of implementing matrix multiplication style computation (convolution, broadcasting, etc.). It may end up being that different engines are most suited for different axes of parallelism (TensorE for determining scores/across multiple sequences).

In fact, managing the memory hierarchy will be, one of the most interesting facets of this project. The NeuronCore architecture has multiple levels of memory hierarchy (PSUM/SBUF/etc) - within a processor and across them - and they’ve just released an even more low level primitive to more directly work with memory to be even faster, so we’ll need to pay very close attention about how we tailor our algorithm to decompose the problem well. Another specific tradeoff, for example, we’ll have to investigate here is if moving data from the GPSIMD engine to the Vector engine is worth it to use the built-in scan operator on the Vector engine. We’d also make large use of the TensorEngine - the chip’s built-in systolic array for a lot of our processing. The data movement may take longer than the extra time the scan operation saves.

In terms of dependencies, to calculate a specific (i,j) cell, as shown in the above diagram, we need the cells previous to it in the row and the cell previous to in the column, as well as the (i-1,j-1) cell. This has a much higher degree of dependencies than previous problems we’ve implemented in 418, but the key is that this is well-suited to systolic arrays. The locality, in the traditional sense, is good across a row, but poor since we need to access values in previous columns. However, depending on our execution model, this may change with the different engines we use. There is no divergent execution to worry about since we execute the same steps for each cell, which means we will not have to worry too much about workload balance. In addition, the communication to computation ratio is high since for a cell, on average, we need to take so many max’s across the array and for each cell. However, since our platform allows us to execute in a SPMD way, this is less of a concern, since we can operate across multiple data at once.

Goals and deliverables

75%-goal: Successfully implement the Smith–Waterman algorithm using the systolic array parallel programming model on AWS Trainium via the Neuron Kernel Interface (NKI). Demonstrate maximum parallelism from this model by designing an efficient dataflow and pipeline synchronization strategy.

100%-goal: Achieve the 75% goal and run the implementation on a dataset that approximates real-world usage (e.g., bioinformatics datasets). Perform detailed profiling to understand performance characteristics, resource utilization, and parallel throughput for real-world dataset on the Trainium platform. Specifically, what is our final computation to communication ratio? How much time are spending moving data? What is the final runtime and how does it scale with the sequence length (i.e. are systolic arrays a good solution for this problem, as the theory suggests they should be).

125%-goal: Compare the profiling results and performance bottlenecks of our systolic implementation with a high-performance CUDA-based Smith–Waterman library (such as CUDASW++). Analyze differences in hardware efficiency, data movement costs, and parallel scalability between the systolic and CUDA execution models OR Extend our implementation to work for multiple sequence alignment (MSA), in which existing solutions use other, less accurate algorithms, because of the inability for Smith-Watterman on existing platforms to scale (it has complexity $L^n$ for $n$ sequences of max length $L$, but the best quality).

Original Schedule

Up-to-date Schedule

| Task | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set up Trainium Environment | ✅ | |||

| Start running NKI examples | ✅ | |||

| Write NKI primitives to use in algorithm | ✅ | |||

| Implement simple SW algorithm in NKI | ✅ | |||

| Profile algorithm to determine optimizations | ✅ | |||

| Implement optimizations on SW algorithms | ✅ | |||

| Start running and profile real workloads | ✅ | |||

| Holistic analysis of varied real/worst-case workloads | ✅ | |||

| [EXTRA] Compare with CUDA library for workload & data movement comparison | ✅ | |||

| [EXTRA] Implement multiple sequence alignment | ✅ |